Fr Gurien Jacquier of Ghogargaon

(Catholic mission in Aurangabad diocese - 1892 onwards)

By Camil Parkhe

camilparkhe@gmail.com

Copyright : SFS Publications

Published by: SFS Publications,

PB No 5639

Rajajinagar, 1st Block,

Bangalore, 560 010

ISBN 81-85376-78-6

First edition 2009

Index

i) Preface- Bishop Edwin Colaco, Aurangabad diocese

ii) Fr Marian Fernandes, MSFS Provincial, Pune Province

iii) Fr Stephen Almeida, parish priest of Ghogargaon

1) A pilgrimage to Ghogargaon

2) Arrival of Christianity in Nizam’s Hyderabad state

3) Ghogargaon – First MSFS mission in Nagpur diocese

4) Fr Marian Thomas, Mission founder

5) Fr Jacquier- From France to Ghogargaon

6) Untouchability and social scenario in 20th century

7) Dalit Christians during pre-independence era

8) Portrait of Fr Gurien Jacquier

9) Boosting morale of Dalit Christians

10) Foundation of Borsar mission

11) World War I: MSFS priests in Jesuits’ Nagar missions

12) Fr Jacquier in Rahata

13) Fr Berger in Kendal

14) Social scenario in Rahata, Sangamner, Kendal

15) A Jesuit’s tribute to MSFS priests

16) Christianity in Marathwada (1915-1923)

17 Fr Forel in Borsar mission

18) Christ the King Church, Ghogargaon

19 Lohgaon-Bidkin mission - Paithan

20) Archbishop Doering’s visit to Ghogargaon

21) A missionary’s dilemma

22) Exploitation of tamasha artistes and Jacquierbaba

23) Jacquierbaba challenges custom of untouchabalility

24) First local vocations: Fr Monteiro, Bro Taide

25) Jacquierbaba in his twilight years

26) Civic reception to Jacquierbaba

27) Called to eternal reward

28) Ghogargaon: Two sons of soil ordained priests

29) Formation of Aurangabad diocese

30) Parishes in Aurangabad (Marathwada) diocese

------

6) Untouchability and social scenario in 20th century

Fr Gurien Jacquier arrived from France in Ghogargaon in Aurangabad district when the 20th century was about to end. The British had by that time established their political rule almost all over India. Aurangabad district was at that time a part of the princely state of the Nizam of Hyderabad. Ghogargaon became Fr Jacquier’s permanent home. He was transferred from there twice but returned to his ‘home’ again where he spent his twilight years and chose this obscure village as his final resting place.

The role played by this missionary in transforming the prevalent social, religious structure would be known only when one takes into consideration the feudal society, the rigid caste structure and the barbarian, inhuman custom of untouchability, called by Mahatma Gandhi as the scourge on humanity. In the 20th century, the human habitation was not found located at one place in the village. Some people preferred to stay on their farms, a cluster some 10 to 12 homes used to locate elsewhere and it was called as Wadi. The central location of the village where a majority of the villagers lived was called as ‘Gaothan’. This main site of the village used to well fortified with a wall and a main tall entrance to protect the villagers from dacoits and other unwanted unscrupulous elements. This fortified wall was called as Gaokusu. Only the people belonging to the high caste were permitted to live within the protected walls of the gaokusu. The others, the outcaste people, were condemned to live beyond the village territory and were allowed to step in the village only when their services were required by the upper echelon.

The high caste community which lived in the village enclosure included those belonging to the first three of the total four varnas or the chaturvarnas. The three varnas which enjoyed social dignity included Brahmins, Kshatriyas and the Vaishyas as described in the Manu Smriti, the law book of Manu. The upper caste community too was divided into various sub-castes and groups, with some groups claiming the superiority of their sub-castes and the others contesting these claims.

The people belonging to the last Varna, Shudras were those who lived outside the village fence wall. The main outcastes, also referred to as untouchables, were the Mahar, Mang and Chambar (cobblers). Besides, there were also some tribes and nomadic tribes which had inferior status in the social structure.

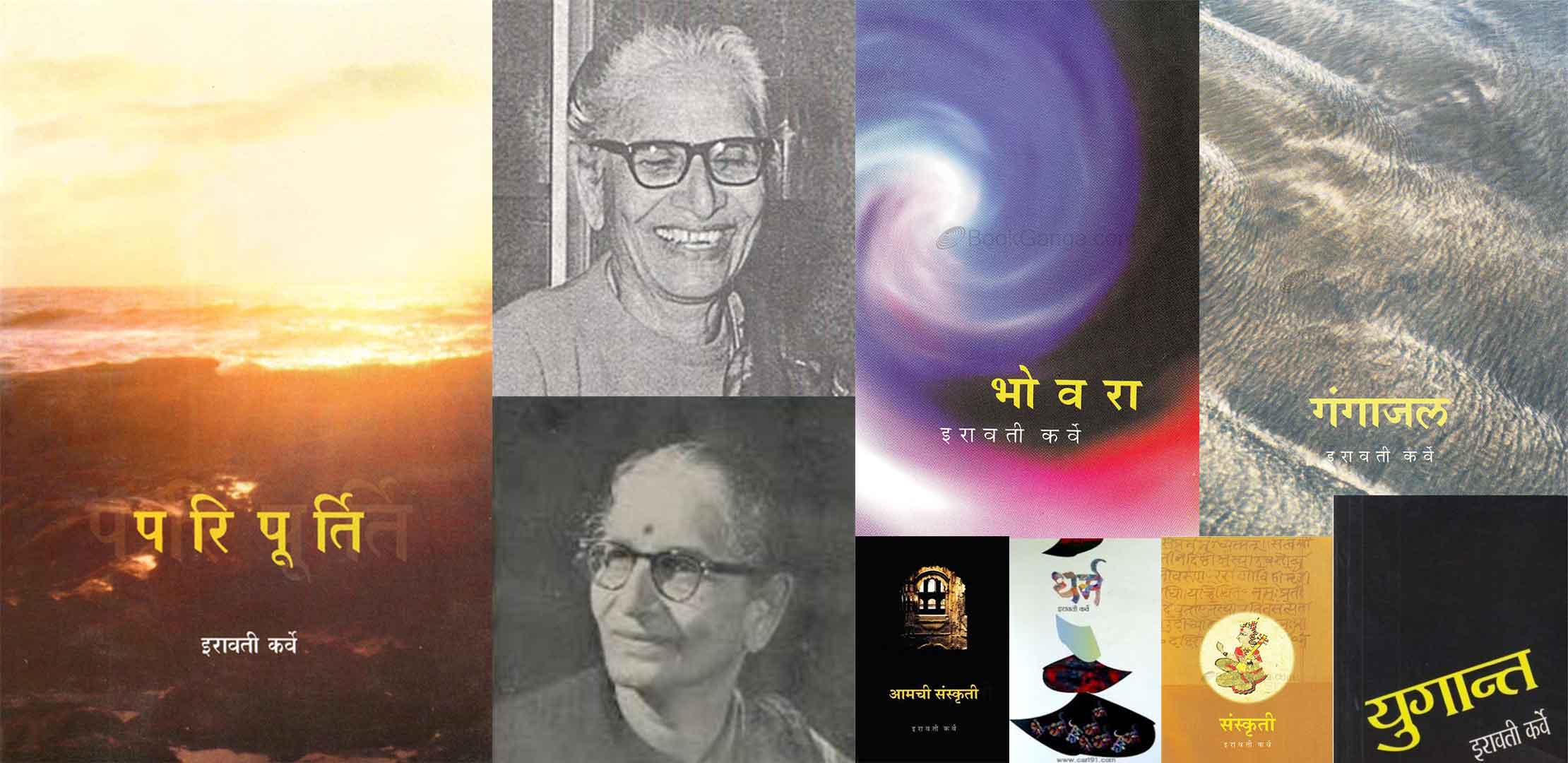

Unlike the other upper and lower castes, the Mahars are found almost in all villages in Maharashtra. According to some scholars, in fact, Maharashtra has earned its name, the Rashtra (nation) of Mahars, from its dominant Mahar population. Veteran anthropologist Dr Iravati Karve has said that except the Mahars, no other caste, not even the Maratha or Kunbi, has its presence in all villages of the Maharashtra state in India. 1

The untouchables are those whose even sight was considered as inauspicious and bad omen and the upper caste people considered it to be a sin to touch them. The upper caste people had to bathe again to purify themselves if any time they accidentally touched the untouchables.

Some books published in Marathi during the early years of the 20th century throw light on the social situation, the caste-based barter system and the condition of the untouchables in Maharashtra during this period. Trimbak Narayan Aatre who had served as a tehsildar during the British regime has written a book in Marathi, entitled ‘Gaogada’, ‘the village chariot’ which was published in 1915. 2

Another relevant book is ‘The Mahar folk- a study of untouchables in Maharashtra’ written by Rev Alexander Robertson and published in 1938. 3

Maharashtrachi Grameen Samajrachana (The Social Structure in Rural Maharashtra)’ is another book, written by economist Dr V M Dandekar and M B Jagtap, his colleague at the Pune-based Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics which throws light on the social structure prevailing in the 1950s when the country had got freed of its political shackles. 4

The horrifying predicament of the untouchable communities is also reflected in the autobiographical writings of the Dalit writers published in Marathi after 1970s.

The settlements of the Mahars and the Mangs, located outside the village’s boundary walls used to be called as the Maharwada or Mangwada, respectively. In Vaijapur and Gangapur talukas of Aurangabad district where Fr Jacquier worked, Maharwada was ironically referred to as the Rajwada (the palace). Many residents of the Maharwadas in these talukas were converted to Christianity by Fr Jacquier and his MSFS priest colleagues. Nonetheless, a century after their conversion, these settlements are referred to as Rajwada even in 2008. So much is the rigidity of the caste system in India.

The villages which had a boundary wall from all sides to protect the villagers from the thugs and dacoits had an entry gate, the Wes. The gates used to be closed after sunset and opened only after the break of the dawn. The wes was guarded by a weskar, a member of the Mahar community. The Weskar would function as a watchman, keeping a close vigil on the people entering and going out of the village. He would also stand as main witness in the event of any civil or criminal dispute in the village.

The settlement of the lower castes and the untouchables was always on the lower directions of the river or steam. This enabled the higher caste people to collect or avail of the flowing water before it was contaminated by the touch of the lower castes people or the untouchables. There was a hierarchy even among the so-called higher castes and the flowing water was consumed as per this social ladder.

Accordingly, the Brahmins who unquestionably stood at the top of the social ladder availed of the river, stream water first, followed by the upper caste people such as the Marathas, goldsmiths, Kunbis, Malis and others. Even the untouchables had hierarchy among themselves and their locations of river/stream water consumption were fixed accordingly. In the lower caste hierarchy, the Ramoshis and Chambhars stood on a higher plain, followed by the Dhor, the Mahar and the Mang. The Bhangis or the scavengers stood at the bottom of this social pyramid. Of course, in practice, the Mahars considered themselves higher than the Mangs or the Chambhars and the vice versa.

When the rivers or the stream dried during the summer and in areas where there were no flowing sources of water, the entire community within the village boundary and the outside had to depend on the wells. Most of the times, each of the upper castes and the lower castes people had their independent wells. The untouchables had to depend totally on the mercy of the higher caste people when they had no wells of their own or when these wells got dried during the summer. The untouchables were forbidden to draw water from the wells meant for the upper castes and they had to wait near the wells for some good soul from the upper castes to take pity on them and pour water on their hands to quench their thirst. But the upper caste man or woman would take care to pour from safe distance lest he or she be defiled by the touch or shadow of the untouchables. In the history of the humankind, no other parts of the world ever had such most inhuman, cruel traditions. Perhaps, even the slaves during the ancient period were treated with more consideration!

The treatment meted out to the untouchables was worse that the treatment given to the slaves during ancient period. The barbarian social practice of untouchability perhaps had only one parallel in the history of human kind – the treatment given to the black people – the people of African race who were denied basic human rights in their countries or in Europe and America on account of the colour of their skin.

It was the total contempt for the inhuman custom of untouchability that led to Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar to launch a stir to open the Chavdar Lake at Mahad in the Konkan region of Maharashtra in 1927. Even after this agitation, the public water bodies in Maharashtra were not thrown open to the untouchables. The high caste people also refused to open the public temples to the Dalits.

This stubborn attitude of the high caste community had led much exasperated Dr Ambedkar to declare his intention in 1927 to give up Hinduism and to embrace another religion which would offer him and his followers a dignified life. Despite his threat, there was no change in the attitude of the higher caste community, forcing Dr Ambedkar and his numerous followers to give up Hinduism and embrace Buddhism in 1956.

“During our survey of 72 villages, we have not come across any incident of the untouchables availing of the water at the public wells in their villages,” wrote veteran economist V M Dandekar and his companion M B Jagtap a few years after India had gained Independence. 5

This was the social situation prevailing when Fr Gurien Jacquier arrived in 1896 to preach the gospel in rural parts of Aurangabad district. The only people who positively responded to him and embraced Christianity were the Mahars, the untouchables. It was indeed a great challenge to socially and spiritually shape this most oppressed community. The French missionary took the gauntlet and did not give up till he breathed his last in the same village five decades later.

References:

1) Iravati Karve, ‘Mahar Ani Maharashtra (Mahar and Maharashtra), ‘Paripurti’ (Marathi), published by Deshmukh and Company Pvt Ltd., 473, Sadashiv Peth, Pune 411 030 (10th edition 1990), (page 74)

2) Trimbak Narayan Aatre, ‘Gaongada’ (Village Cycle) Publishers: H A Bhave, Warada Books, 397/1, Senapati Bapat Road, Pune 411 016 (Third edition, reprinting 1995)

3) Alexander Robertson, ‘The Mahar Folk- A study of untouchables in Maharashtra – The religious life of India series’; Publishers- Y M C A Publishing House, 5 Russell Street, Kolkata, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press (first edition 1938), second edition published in 2005 by Dr Ashok Gaikwad, Kaushalya Prakashan, N-11, C-3/24/3, HUDCO, Aurangabad (Maharashtra)

4) V M Dandekar and M B Jagtap, ‘Maharashtrachi Grameen Samajrachana (The Social Structure in Rural Maharashtra), Published by D R Gadgil, Gokhale Institute of Economics, Pune (1957)

5) As above; Page 10